Course:

The Cuban Literacy Campaign

This content has been extracted from the DNS curriculum which shows students what the Cuban literacy campaign and its ethics in the 1960s was about, a reform which became a model and inspiration for many countries around the world.

The dictator Fulgencio Batista was finally overthrown on January 1, 1959, by the armed guerrilla known as the 26th of July Movement (Movimiento 26 de Julio).

During the turmoil of the first several years of the revolution, the flight of many skilled workers caused a “brain drain.”

The newly instated revolutionary government, led by Fidel Castro, immediately began a series of social and economic reforms. Among these was the agrarian reform, the health care reform, and education reform, all of which dramatically improved the quality of life among the lowest sectors of Cuban society.

The loss of human capital had prompted renovation of the Cuban education system to accommodate the instruction of new workers who would take the place of those who had emigrated from the country.

In addition to the renewal of Cuba’s infrastructure, there were strong ideological reasons for an education reform. In pre-Revolutionary Cuba, there was a severe dichotomy between urban citizens and rural citizens who were most often agricultural workers. The Cuban Revolution was driven by a call for equality, particularly among these two classes.

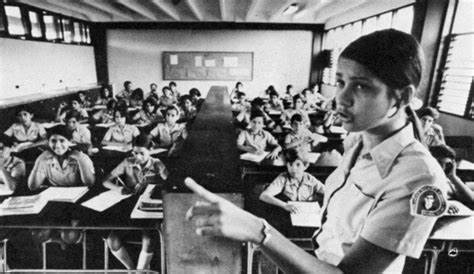

The Literacy Campaign was designed to force contact between the separate sectors of society. So, the government placed urban teachers in rural environments where they were pressed to become more like the peasants in order to break down social barriers.

Fidel Castro put it in the hands of the people in 1961 while addressing literacy teachers, “You will teach, and you will learn.” Volunteers from the city were often ignorant of the poor conditions of their fellow rural citizens until they ventured out in this campaign.

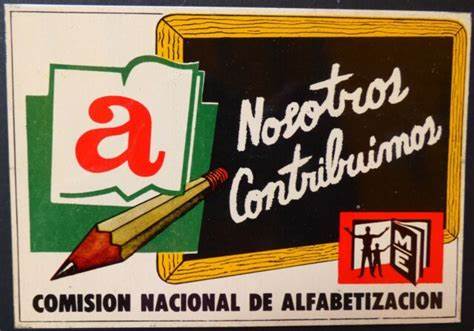

Besides literacy, the campaign aimed to create a collective identity, one of unity, with an attitude of combat, courage, intelligence, and a sense of historical awareness. Politicized educational materials were used to further these ideals. Furthermore, Castro went as far as to state a need for the rural populations to take on the roles of teachers in order to expand education in the urban populations. The effort was labelled a movement of the people and gave citizens a common goal with increasing solidarity. “Literacy brigades” comprised young students who were sent out into the countryside to build schools, train new teachers, and teach the local population how to read and write.

Before the campaign, the rate of literacy among city dwellers was 11% compared to 41.7% in the countryside.

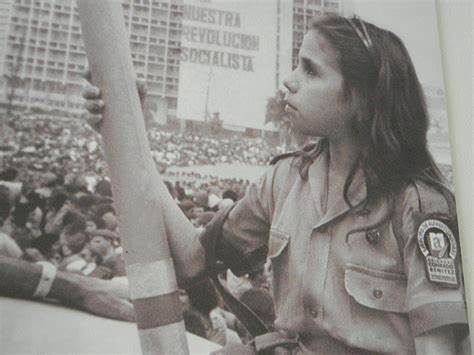

On December 22nd, 1961, a hundred thousand (100.000) literacy teachers marched to the Plaza de la Revolucion, carrying giant pencils and chanting: “Fidel, Fidel, tell us what else we can do!”

To which Fidel Castro famously replied: “Study, study, study!”

Fidel Castro’s government decided that 1961 would be the ‘year of education’, in an attempt to raise Cuba’s literacy rate, which was round 77% in 1959. The Cuban Literacy Campaign was an eight-month long struggle to eradicate illiteracy during the recovery from the Revolution.

*(Adult literacy rate is the percentage of people ages 15 and above who can both read and write with an understanding of a short simple statement about their everyday life.)

By 1962, the country’s literacy rate increased to 96,1%, one of the highest in the world.

Cuba literacy rate for 1981 was 97.85%.

Cuba literacy rate for 2002 was 99.80%, a 1.95% increase from 1981.

Cuba literacy rate for 2012 was 99.75%, a 0.05% decline from 2002.

In 2012, Cuba’s literacy rate reached 99,75%. The Cuban literacy campaign became a model of inspiration for many educational projects around the world, and it lived on as a celebrated and meaningful example.

The campaign was indeed a fascinating chapter in History and a great testament to what the power of enthusiastic, committed people can achieve.

However, another relevant aspect to the campaign was the part played by young women, who transgressed very established gender roles of the time, many times against the will of their families, joining the “army” of literacy teachers.

Designed as a real war against illiteracy: the volunteers were regarded as soldiers and provided military clothing, regardless of their gender.

Towards the end of the Literacy Campaign, in the conventional scholarly narrative of gender in post-revolutionary Cuba is that the revolutionary government prevented the emergence of an expressly feminist movement by addressing women’s basic needs and simultaneously eliminating autonomous space for females organising.

Recent scholarship has increasingly considered women’s participation in revolutions in order to understand women’s roles in post-revolutionary societies. An analysis of the testimonies of female former volunteer teachers and of the official rhetoric and content of the campaign suggests that the broader narrative of cooperation, while certainly accurate overall, threatens to obscure instances in which women did challenge traditional gender norms in meaningful ways.

Today, the Museum for the National Literacy Campaign located in the suburbs of Havana contains thank-you letters to Fidel Castro, photographs of all one hundred thousand (100.000) volunteers (the Brigadistas), samples of the manuals for the Brigadistas, what the books meant for their students, and newspaper cut-outs from that time (Morejon Martinez, 2008).

This paper argues that the Cuban Literacy Campaign and the participation of women in the campaign significantly impacted Cuban patriarchal culture at a pivotal moment. In other words, though a male-led revolution did not give women the space to organise against patriarchy, rather by actively participating in the revolution women helped change the actual nature of Cuban patriarchy today.

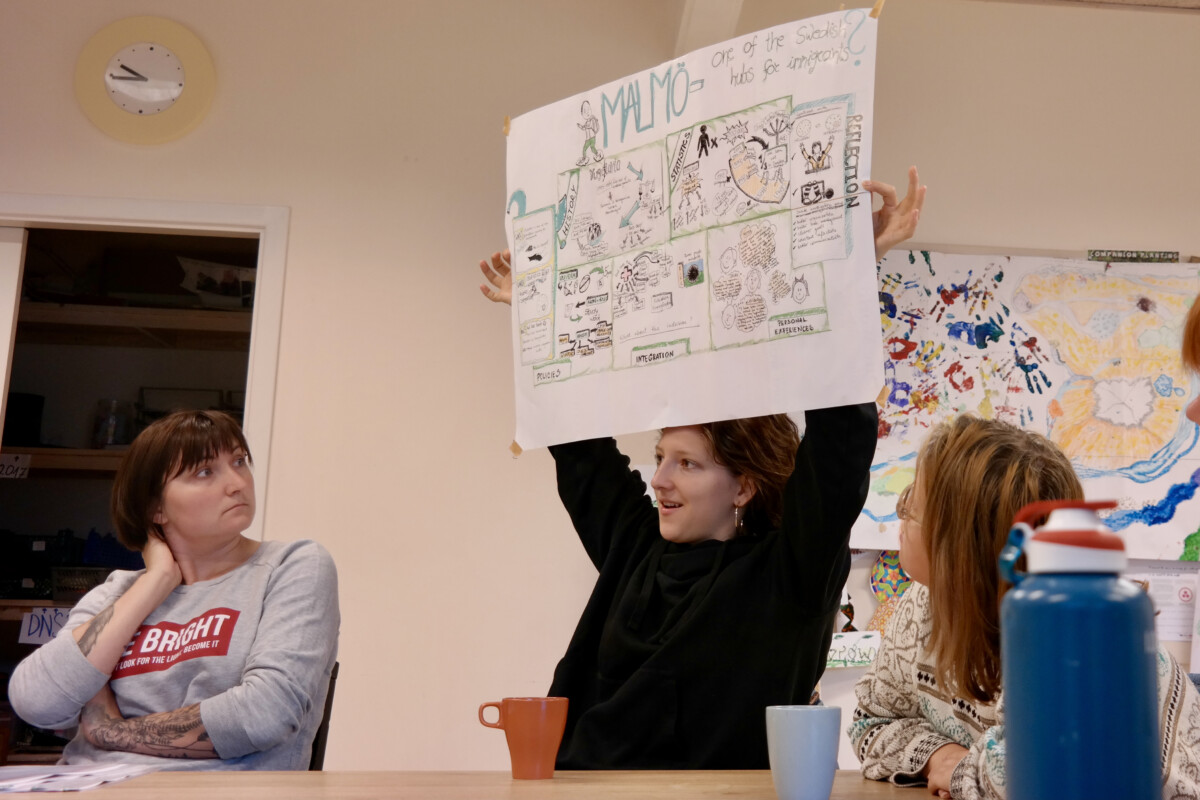

Other Pedagogical Tools

Field Investigations are just one of the unconventional pedagogical methods we practice at our Teacher Training College. Check out this article about 5 interesting teaching tools.

Alternative education

If you are interested in Alternative Education, you might want to read about the 10 pedagogical principles that lay at the base of our alternative pedagogy.

What is DNS?

“The Necessary Teacher Training College” is an alternative higher education aiming to train progressive personalities who are able to understand and respond to the many challenges of our times.

Based in Denmark, our 4-year Bachelor Programme aims to enable its students to become global citizens and proficient educators.

Since DNS was established in 1972, over 1.000 graduates have played an important role in bringing equitable quality education to children and youth, as well as in all sorts of other projects and development programmes worldwide.

Student experiences: “What really causes Climate Change”

What are the causes of climate problems? How does the global warming work? What are all the things that humans do that negatively affect the climate, and how do they compare? What are some potential solutions to these problems, and how should they be addressed?

Three examples of “Learning by Doing”

What does ‘Learning by Doing’ mean? In this article, we explain how this method can be applied to different learning contexts through 3 examples.

What does it mean to lead a “teacher lifestyle”?

Being a teacher is not only a profession – it is a mindset and a lifestyle, too. What does it look like, then, and why should you consider it?

Let’s start a discussion!

Did you like this article? Let us know what you think in a comment!

“It’s by actively participating when the change of things happen.”

Here is what others think:

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

Student experiences: “What really causes Climate Change”

What are the causes of climate problems? How does the global warming work? What are all the things that humans do that negatively affect the climate, and how do they compare? What are some potential solutions to these problems, and how should they be addressed?

Three examples of “Learning by Doing”

What does ‘Learning by Doing’ mean? In this article, we explain how this method can be applied to different learning contexts through 3 examples.

What does it mean to lead a “teacher lifestyle”?

Being a teacher is not only a profession – it is a mindset and a lifestyle, too. What does it look like, then, and why should you consider it?

nice article